November 29, 2021

In Jordan, to Grandmother’s House We Go

How three sisters are using their grandmother’s old recipes to inspire real change in the Jordanian capital of Amman.

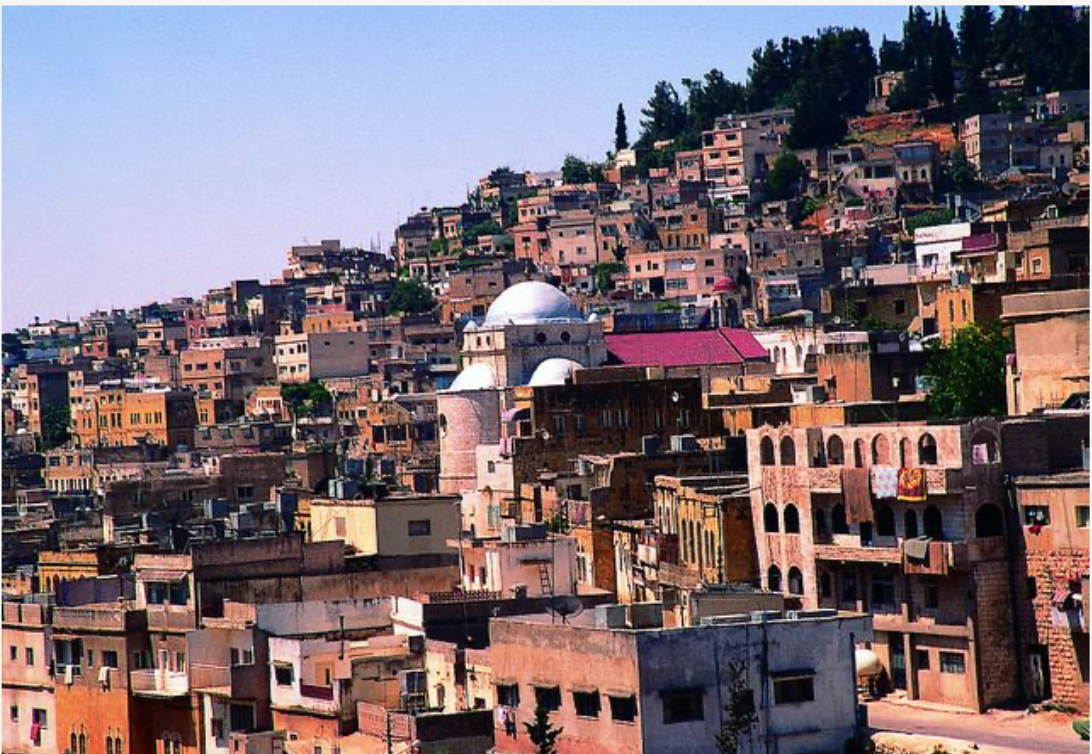

The noise hits you as soon as you enter the souk: a cacophony of male voices, singing the succulent merits of their wares. Juicy tomatoes; plump eggplants; buxom bulbs of garlic. Every vegetable has its own “selling song” here in the Jordanian capital of Amman, and they’re all being chanted at full, throaty volume in the bustling marketplace, like a gravelly garden symphony.

Gliding through this boisterous melee in Souk el-Khodra—the city’s historic fruit and vegetable market—is Maria Haddad, who moves with all the effortless elan of a local, while appraising the produce with the eye of a professional chef.

“I love it down here,” says Maria, as she stuffs a chunky fistful of spinach into her bag and pays the crooning vendor. “Everything is so fresh and full of flavor; the entire place is so alive.”

Maria, 36, is the second of three sisters running a unique business here in Amman: Beit Sitti, which translates from Arabic as “Grandmother’s House.” Inheriting the house in question from their beloved grandmother in 2010, the sisters hit on the perfect business model to honor her memory.

“When we were young, we used to go to our grandmother’s house to learn how to cook Arabic food,” says Maria, as we emerge from the souk, laden with bags of fresh ingredients. “When she passed away, we wanted to keep her memory alive by opening up her house to guests. We teach other people the dishes that she taught us.”

But Beit Sitti (pronounced “Bait City”) is about more than just sharing Jordanian dishes. In a country where working women are still considered taboo across large sections of this patriarchal society, it’s also about female empowerment. Maria and her sisters Dina and Tania employ dozens of local women to help teach the classes, providing them with an income to sustain their families—as well as invaluable entrepreneurial experience. Many have gone on to set up their own catering businesses, something the sisters actively encourage.

“It’s all about supporting these women and giving them their first taste of independence,” says Maria, as we approach her grandmother’s house in the lively Jabal Al Weibdeh neighborhood. “When they come to Beit Sitti, usually on a discrete word of mouth recommendation, many of the cooks don’t want their families to know what they’re doing. But when they start making money and realizing they can rely on themselves, their confidence grows. They arrive timid, but they emerge as businesswomen.”

One of these cooks, a middle-aged woman named Um Reem Amal, is waiting to greet us as we arrive at Beit Sitti. None of the family lives here now, but clusters of framed, black-and-white photographs crowd the walls, while a vintage Singer sewing machine gleams in a corner. French doors open onto a sundrenched terrace, where two kittens chase each other around a lemon tree.

Um Reem helps us unpack and we get to work: chopping, dicing, kneading, shaping, and stirring as we prepare mutabal (a Middle Eastern eggplant dip), a loaded farro salad, and fresh khubz, or Arabic bread. Then it’s time for the main event: maqlubah—a traditional farmers’ recipe that involves mixing chicken, rice, fried vegetables, and spices together in a pot, which is then flipped upside down to serve (“maqlubah” literally translates as “upside down”).

“Everybody thinks that Arabic food is just hummus, falafel, and kebabs, but it’s so much more,” says Maria. “The dishes we’re making today are the dishes that real Jordanians eat at home.”

Throughout the entire hour-long cooking session, we chat about anything and everything, from local celebrities to the local spices that make Jordanian cuisine so flavorsome. (We use several in our dishes, including za’atar, sumac, and the deceptively powerful orange blossom water.) I hear how Um Reem discovered Beit Sitti by accident, while walking past the steps to the house one afternoon, smelling the food and enquiring what they were making. And I also hear about the incredible breadth of clients who have attended these classes, from British celebrity chefs to members of the Jordanian royal family, as well as tourists from as far afield as Chile, China, and Australia.

Finally, sitting on the terrace overlooking Amman in glorious late afternoon sunshine, we get to enjoy the fruits of our labors. The maqlubah, in particular, is so fresh that it seems held together in its inverted glory by sheer force of will. The hot, flat Arabic bread, served straight from the outdoor oven, is another unforgettable treat, and a delight to dip into the rich, creamy mutabal.

“It was hard when we were starting this business in our 20s: Every time we would go to a government agency we’d come back crying,” says Maria, as the kittens eye her leftovers. “In the end, my mother came with us and sat there for five hours, refusing to move until the paperwork was signed.

“Things are genuinely starting to change for working women here now though, and a big part of that has been Queen Rania herself, who has introduced a number of initiatives to help community empowerment. I’m just glad that we could play our part in helping that process along.”

It’s a common Middle Eastern adage that Amman—which dates back to 5000 B.C.E.—is an old city with a warm heart. And in many ways, Beit Sitti is the perfect encapsulation of that welcoming.

“We have a motto here: Cooking breaks barriers,” Maria says. “When you’re cooking with someone else, you automatically start talking to them, and any awkwardness evaporates. The most important thing about Beit Sitti is not learning a new recipe—it’s building a human connection. Maybe that’s what our grandmother was trying to teach us all along.”

Cooking classes at Beit Sitti take place seven days a week, costing $70 per couple or $140 for one-on-one cooking lessons. For more, or to book, visit beitsitti.com.